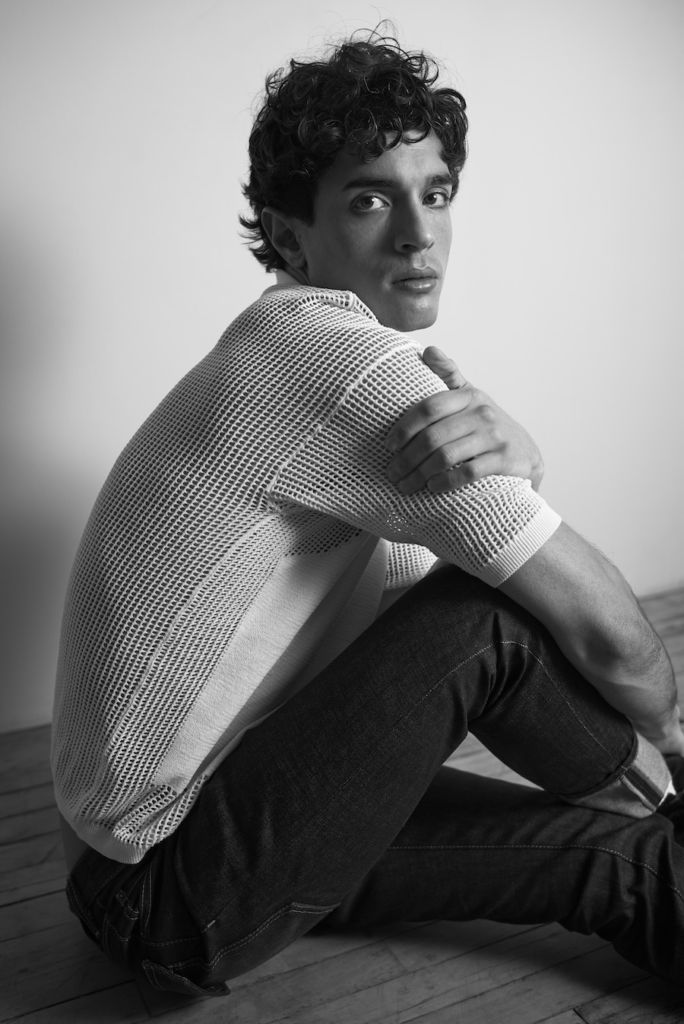

Actor James Cusati-Moyer Bares All

Meet the Slave Play alum who wants to adapt Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life.

Actor James Cusati-Moyer is clear about the kinds of parts he wants. “As an out, queer actor, it’s very important to me to challenge Hollywood’s internalized homophobia,” he says. “Which we’ve seen time and time again [in] lead, queer roles being given to heterosexual-identifying performers.” Institutional bias be damned, the actor, 30, is more energized in his queer-centering project than ever: As a key player in Slave Play, Cusati-Moyer relished the chance to enact radical representation onstage. “It eliminated any sort of fear in my brain,” Cusati-Moyer says of the play, written by fellow Yale Drama whiz Jeremy O. Harris. “I may always feel a certain level of insecurity, but in terms of performing, there was a lot of fear that was worked out of my instrument.”

Though the show won buzz and praise for the density of its non-normative elements, it also, at times, tested Cusati-Moyer’s resolve. Once, during a memorable sequence involving Cusati-Moyer’s character engaged in sub-dom roleplay, verbal fisticuffs broke out in the audience. “I was so distracted and upset that I shouted, ‘Get out.’ Luckily, the audience applauded [in support], and we continued with what we were doing on stage,” he recalls, referring to scene partner Ato Blankson-Wood. “…Which was a sexual act. It was chaotic but memorable [performance], for sure.”

However unfortunate, the episode seemed a pantomiming of Cusati-Moyer’s emphatic mission: to portray queer life in art—by use of force if necessary. Having acted in theater since childhood, Cusati-Moyer, who also came out in early life, has encountered his fair share of detractors. Following a role as a male hustler, Cusati-Moyer’s then-agent dissuaded him from taking on more queer roles. And, before graduating from Yale School of Drama, he’d been somewhat inexplicably expelled from a New York conservatory—the basis being the alleged physical toll of the former dancer’s years of performing. “They saw certain issues with [my] posture and turn-out, how I walked into a room,” he recalls. “They really harped on that, but it was basically [something] to the effect of, ‘We don’t think you’re a good enough actor and we don’t think you’ll make it.’”

Today, the Philly native frames such setbacks as motivational fodder. Post-expulsion, the once-struggling thespian found himself adrift in a kind of New York bohemia—encountering “messy,” sometimes “dangerous” situations that only stoked his hardscrabble work ethic. “Whenever anyone puts a plate of rejection in front of me, my survival instinct is to leave that table and find somewhere else to sit,” he says. “[Getting] kicked out [of school] was kind of the greatest thing that ever happened to me.”

He would eventually make a fruitful return to institutional learning: In his time at Yale, he’d land an agent and meet Harris, thereby planting the seed for his part in Slave Play. But before Harris wrote the role of “Dustin” with Cusati-Moyer in mind, the actor nearly missed out on his Broadway debut: a 2017 production of Six Degrees. “The casting director wrote back to my agent, saying that the role wasn’t right for me…[So] I reached out to [every connection I could] to bust myself into that room,” he says. “I had to challenge their preconceived notions of [me]. If I hadn’t done that, I don’t know where I would be today.”

In scoping out future roles, Cusati-Moyer draws on both his imagination and lived experience. One queer-centric dream project he puts forth is A Little Life, Hanya Yanagihara’s infant-sized, contemporary epic. “I attached myself to Jude the most—his heart and his humanity sort of tore me apart inside,” he says, referring to the book’s pained protagonist. “To be perfectly frank, I come from a history of abuse and addiction, when I first read it I was like, ‘Oh god…’”

If his willingness to tackle personal pain is an indication, Cusati-Moyer seems a worthy heir to the ever-expanding mantle of queer storytelling. “Any stories pierce you or give you a sense of discomfort—that’s how you deal with [your own] pain, and get through those feelings,” he attests. “Those stories don’t turn me off; they’re the ones that attract me.”

Discover More