Bruce LaBruce Talks ‘Death Book II’

The Canadian artist explains the importance of being shocking in 2020

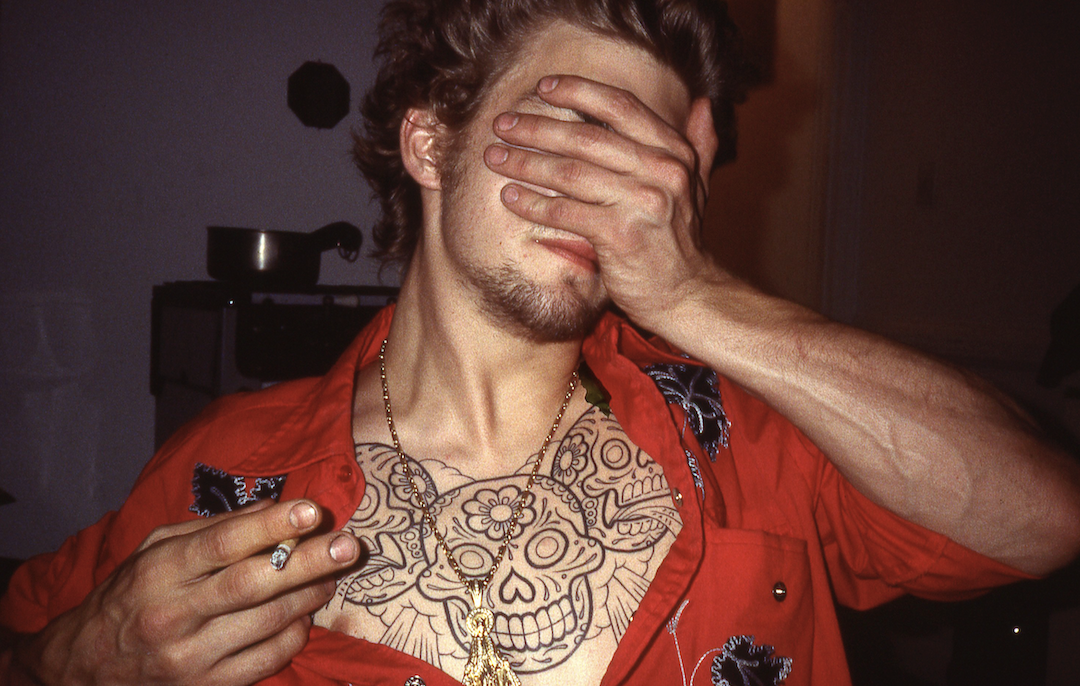

Bruce LaBruce’s latest project continues the Canadian artist’s plight to push boundaries. The second installment of his Death Book is a dark but playful look at familiar Western life but remixed with horror, death, and gore—seemingly, obsessions of the mind that created the images across the book’s pages. Filled with rare visuals from performances, film production stills, photoshoots, and various other moments from LaBruce’s already lengthy career, the book features the likes of Francois Sagat and Dash Snow, amongst others. With art direction from Max Siedentopf, Death Book also comes with an intro by artist, writer, and collaborator Slava Mogutin.

We spoke to LaBruce about the new book and why it’s especially important to be shocking at this particular moment in history.

Mathias Rosenzweig: Is the new book a collection of unpublished work or have we seen some of it before?

Bruce LaBruce: It’s a mixture. There’s quite a lot of previously unpublished stuff. There are a few things I did specifically for the book and then there are images that have been floating around for a long time that I’m kind of associated with, that are kind of trademark images of mine.

MR: The classics.

BL: [There’s] some stuff I shot for porno shoots, for the porn magazines in New York, like Honcho and Inches and Playguy. So some of those images became representative of my work from that era, which is like the late ‘90s and early 2000s.

I also do events at either my own gallery openings or specifically as an event at a gallery. There are also images from that. They’re live or performative, photoshoots and polaroid shoots where I got models to come in and dress as either revolutionaries or zombies or revolutionary zombies, or some sort of abduction motif, or ISIS videos. I was referencing beheading videos and stuff like that. I invite members of the public to the gallery to participate in the photos. I would do polaroids and sign them and keep one and give one to the subject. So they leave with a little piece of art, but they’re usually very violent and scenarios of like, torture, but they’re very playful, and the atmosphere is not negative. It’s a fun, cathartic, playful atmosphere. I used fake blood and sometimes gore and splatter. So ultimately, that stuff is really fun. Especially when it’s analog—like dipping your hand into a bucket of gore or fake blood. There’s like an aspect of play there, that you don’t find with digital.

MR: I imagine it’s a world of difference.

BL: CGI is very cold and kind of dead-looking.

MR: I’d imagine that even during shooting, there’s a big difference between telling someone to pretend they’re covered in blood versus actually covering them in something.

BL: It’s almost it’s like [the film] Carrie but fun Carrie. I sort of consider myself a radical pragmatist. Now, I certainly don’t identify with the Right at all, but my work has always critiqued the Left very strongly. And that quite often is even more shocking than showing something extremely pornographic or violent. You know? So, I think that’s where you can be more shocking, is to just not follow the party line and instead to add challenging ideas of what isn’t progressive. The Left has become kind of Stalinist, and the Right is Fascist. There’s censorship and policing language and desire and queer representation. So that’s my struggle now. I’m totally into John Water’s idea of shock value, like shock for its own sake. Like I said, it’s fun.

It makes people question their own limitations. It makes me question my own limitations. When I make a film or do a photo shoot or something where I get that feeling like, “Oh my god, I’ve really gone too far this time,” in a way it’s scary, but it also sometimes indicates that you’re on the right track. You’re doing something that maybe hasn’t been seen before, or that challenges your own assumptions what you can and cannot represent. So it’s a personal kind of challenge as well.

MR: Why is it important to still push boundaries?

BL: Because we’re in a very regressive time, and what this era should teach people is that nothing is guaranteed in terms of progressive politics, in terms of the acceptance of LGBTQ people. And I use Poland as an example. In the late ‘90s, I was invited to Warsaw and showed my movies in attics and basements. Because it was that against the law, and you could be prosecuted for it. Then about 10 years later World Pride was in Warsaw, I believe, and then 10 years after that we’re back almost to square one. From what I gather. It’s homophobic and anti-gay right. So that’s very instructive to me. I mean you can’t take anything for granted. You can’t just say, “Oh no! things are different and I can do whatever I want, and my rights are guaranteed,” and all that kind of stuff. And then along with that, it’s also this tendency of assimilation just to really say, “Okay, we have to be well-behaved, we have to not be seen as something radical or rowdy, or unruly, we have to step in line,” and that is dangerous too because it’s just conformity. It’s a different kind of conformity.

MR: When I was younger I thought progression was a linear thing. Now I’ve learned it’s fairly erratic, so I get your point. What do you have coming up next?

MR: When I was younger I thought progression was a linear thing. Now I’ve learned it’s fairly erratic, so I get your point. What do you have coming up next?

BL: I have Saint-Narcisse, my movie, now playing the festival circuit. And the DEATH book is shipping now.

MR: So you’re staying busy then?

BL: That I am.

Discover More